Beyond the Individual: Exploring Collective Intelligence with SCIoI at Berlin Science Week 2025

How can intelligent behavior emerge from interaction and coordination within groups? The topic of collective intelligence is deeply fascinating. Among SCIoI’s contributions to Berlin Science Week 2025 was one event devoted to this line of research, offering a general audience insight into the underlying question.

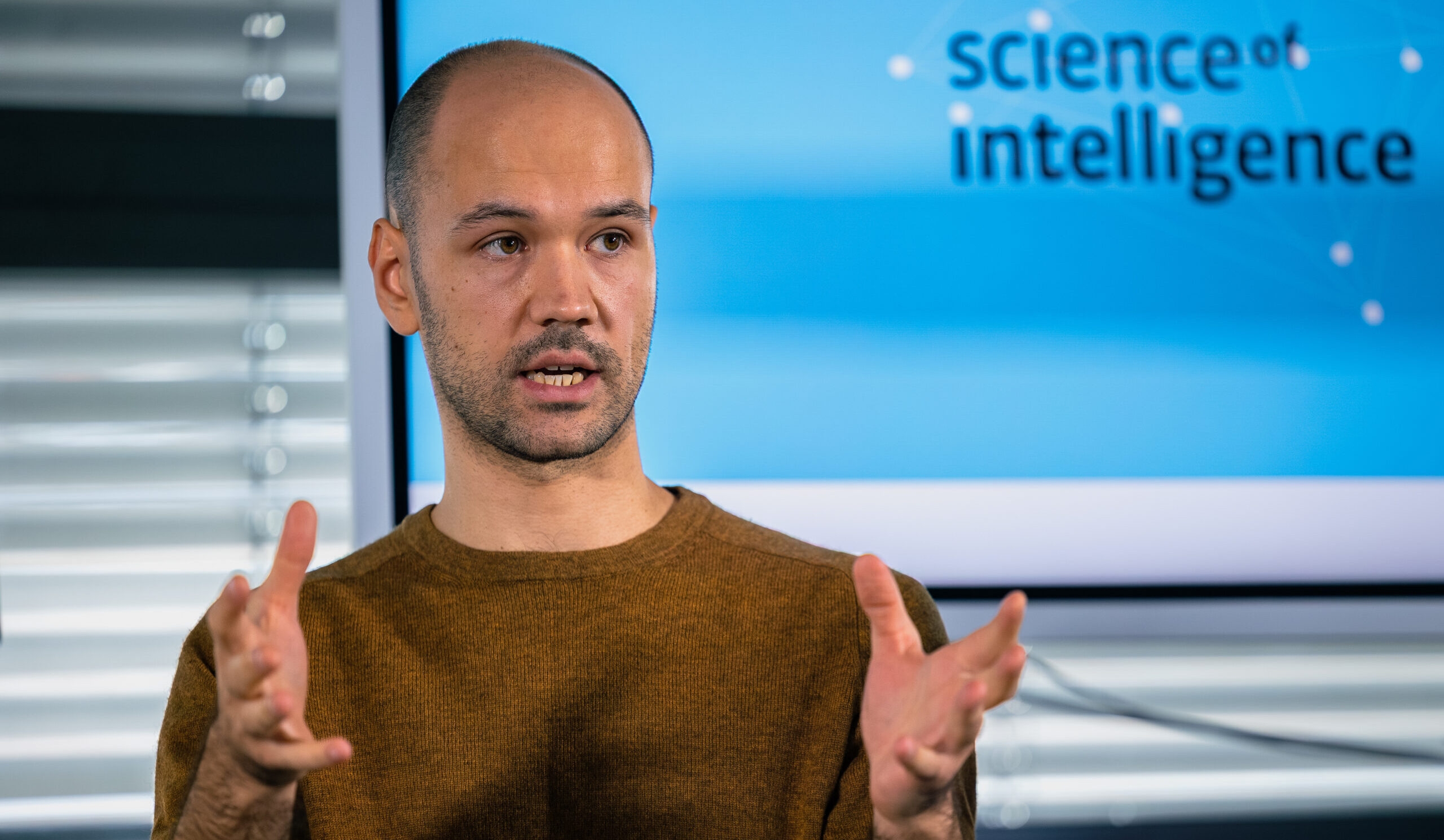

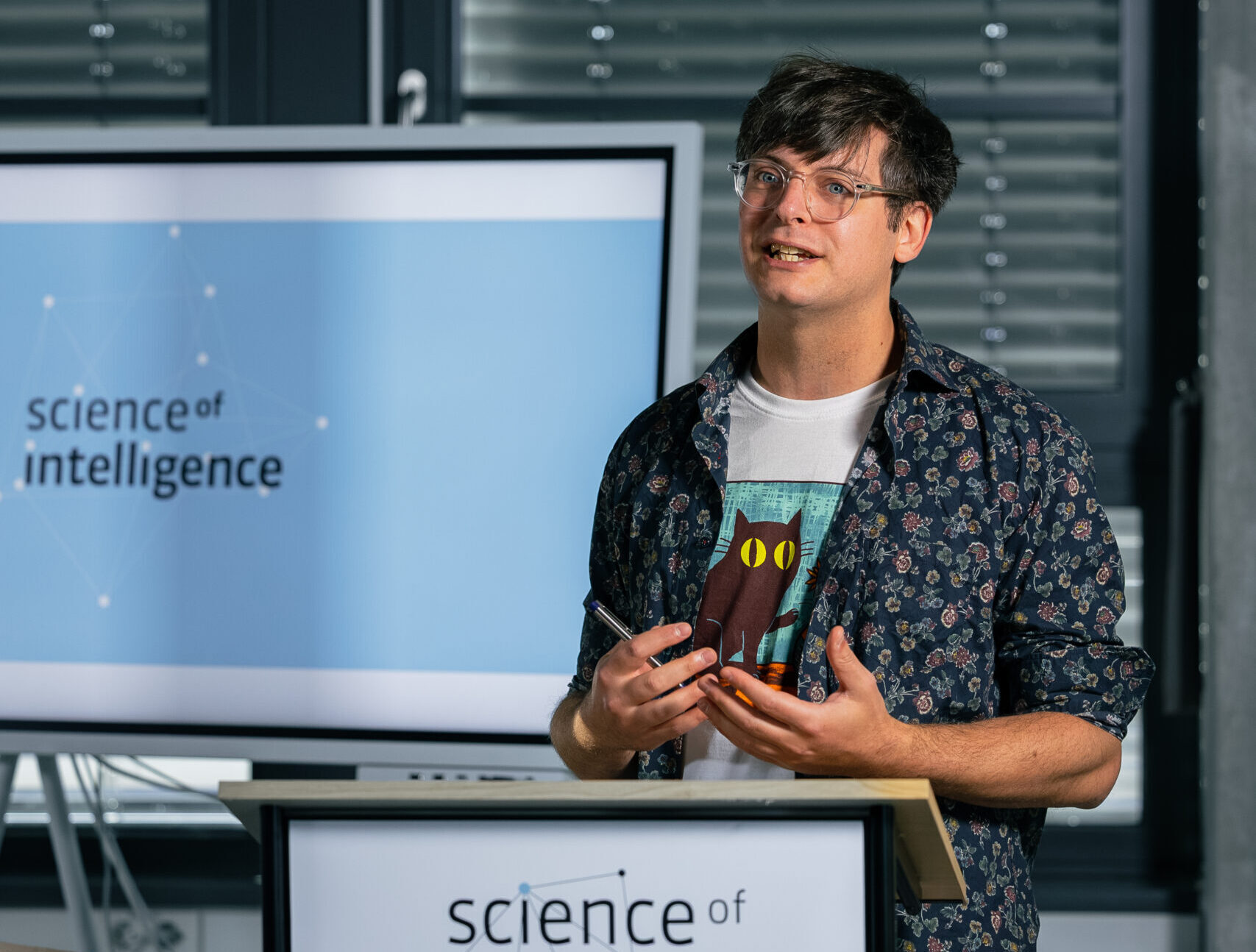

Computer scientist Palina Bartashevich opened the event with a public talk that set the conceptual frame and joined the following panel discussion with philosopher Marten Kaas, computational cognitive scientist Valerii Chirkov, physicist Yunus Sevinchan, and swarm roboticist Yating Zheng. Together, they discussed collective intelligence across natural systems, artificial swarms, and human societies, focusing on how groups solve problems through interaction.

Intelligence between minds

Palina opened by challenging an ingrained image of intelligence as something that happens inside a single head. “We often imagine intelligence as an individual planning moves ahead, like in a chess game,” she said. “But when we look at natural systems, we see “intelligence” emerging from interactions.”

From ant colonies to bird flocks, she argued, highly coordinated behavior can arise without central control. “No single ant understands the whole colony, but collectively they solve complex problems,” she told the audience. “So maybe intelligence doesn’t only happen inside a single brain. Maybe it also happens between individuals—in their connections, interactions, and shared information. That’s what we call collective intelligence.”