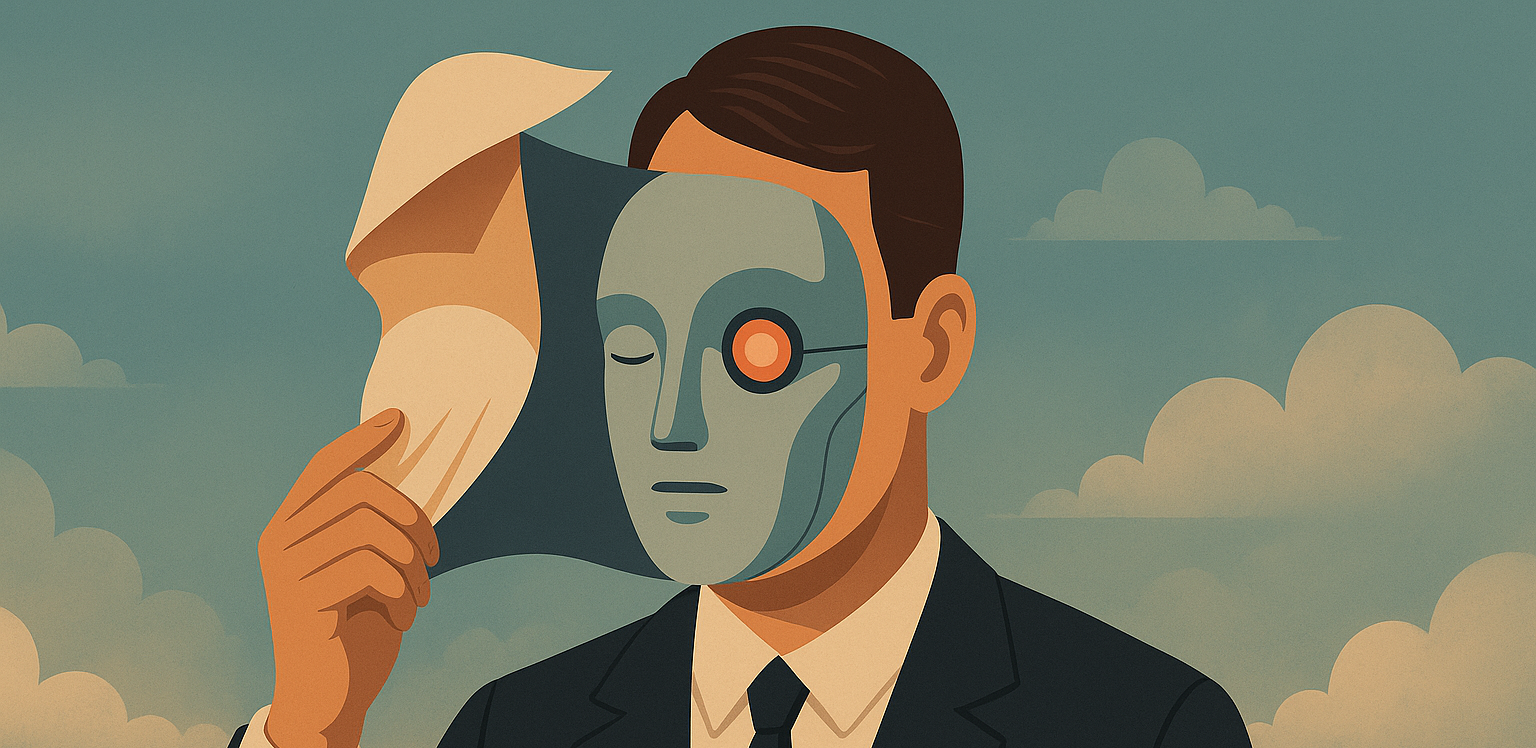

Friendly or hostile? What our brains see in robot faces

How do we decide whether to trust a robot? What makes us see intention in a mechanical face? Researchers from Science of Intelligence have found that our impressions of social robots are shaped not only by their actual appearance but also by what we believe about their behavior. Their study “Neural dynamics of mental state attribution to social robot faces”, published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, shows that when people are told a robot behaves helpfully or harmfully, they quickly begin attributing mental states and emotional expressions, even if the robot’s face remains unchanged.

Two experiments: Judging the same face differently

Researchers Martin Maier, Alexander Leonhardt, Florian Blume, Pia Bideau, Olaf Hellwich, and Rasha Abdel Rahman from SCIoI conducted two complementary experiments. In the first, an online study with 60 participants (30 German and 30 English speakers), robot faces were shown alongside short audio stories that described their actions as either positive, neutral, or negative. Afterwards, participants rated the robot’s facial expression and trustworthiness. The same neutral robot face was perceived as friendlier or more hostile depending on what the participant had previously learned about its behavior.

In the second experiment, EEG recordings were used to track how these impressions were reflected in the brain. After a learning phase where participants memorized the same behavioral stories, they viewed the robot faces again while their brain activity was recorded. This method allowed the researchers to observe the timing and stages of mental state attribution at the neural level.