Multi-timescale computation

Intelligent beings adapt to changes in the environment, but also to variations in the timescales at which the environment changes. A natural example of this is given by the way vision works in an intelligent system, and by how the system controls selective attention and moving gaze in dynamic scenes. The eye operates on a very fast timescale. Its quick movements help our brain get a general picture of what is currently contained in the scene, and this happens within a very short timescale. On a longer timescale, however, the brain also keeps track of the scenes or parts thereof it has already looked at previously and uses memory to avoid going back to the same salient or noticeable thing over and over. The brain also keeps track of the changes in the environment, adapting to new situations and making use of different scales of time to efficiently analyze the scene.

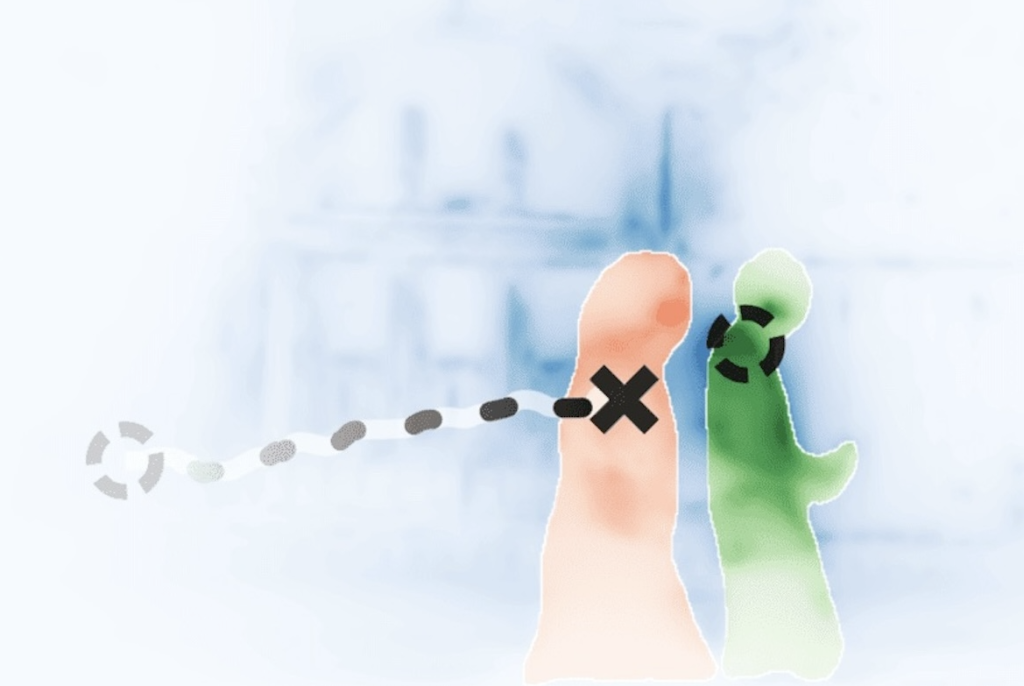

Another example of this is brought to us by the findings from SCIoI project 41, which describes the peculiar behavior of a fish collective living in a Mexican pond. When a bird approaches, the intelligent system, in this case the swarm itself, goes into a state of excitability (known as criticality) which brings the fish to collectively dive down, forming a very quick wave that startles the predator and normally discourages the attack. However, after this initial quick startle effect, the wave continues in a different form for minutes, discouraging the bird from further attacks. The swarm thus proves to be able to operate on different timescales as an adaptation to its environment.

Sulphur mollies respond to the kingfisher’s attack by forming a first quick wave followed by a set of waves, presumably to disorient the bird