What would a non-intelligent entity do?

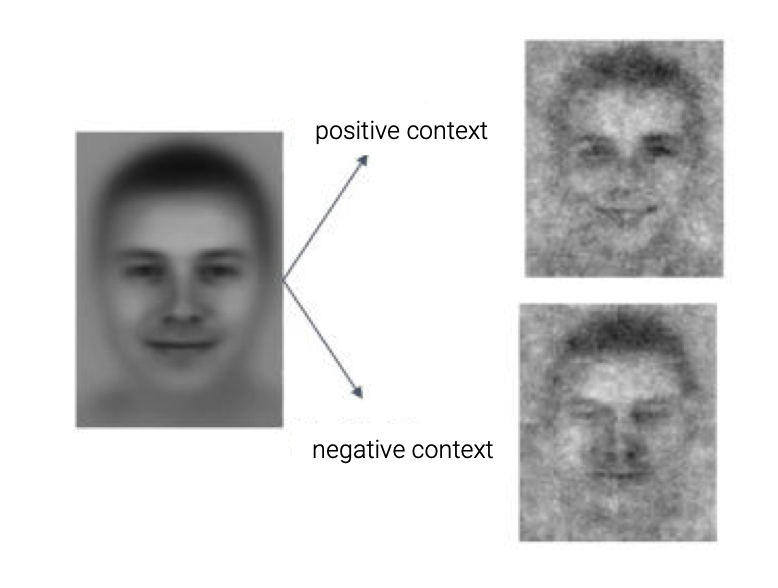

For better understanding it is useful to make a comparison with non intelligent counterparts of the examples above. In this case, a non-intelligent engineering artefact such as a face recognition camera would still recognize the face and its features, but would not be able to adapt its interpretation to its previous experience, or to give bigger weight to certain features based on memory of task.

A more in-depth look

Sensations of the world and actions operating on the world are affected by many factors, e.g., objects, lighting, or the agent’s posture. Perfect knowledge of these processes could, in theory, lead to a disentangled representation, i.e., a representation whose components are fully independent of each other. This idealized situation cannot be achieved, since information about the world is always uncertain and partial. As a result, the representations of an intelligent agent are always approximations to ideal representations. Given a particular task, one can identify a “good” representation for which the relevant factors are more disentangled than in others. Since such “good” representations will depend on the task, an intelligent agent must possess adaptive representations. On a mechanistic level, representational adaptation can be realized by adjusting the weighting of features. For example, when grasping a cup, grasp-relevant features such as shape are more strongly weighted than grasp-irrelevant features such as color. The differential weighting of information is related to an altered information flow between components in the system (see active interconnections). While adaptive representations are a crucial property of individual and social intelligence, how much explanatory power they hold for collective intelligence is still an open question.

Related projects

Project 8: Knowledge-augmented face perception